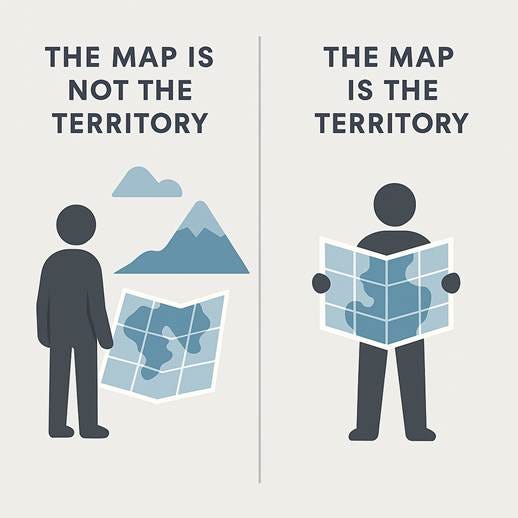

Finding Freedom, Part 1: The Map is Not The Territory

Humans have been drawing maps for a very long time, ever since we began carving them into mammoth tusks some 27,000 years ago. Since then, we have been creating maps of all sorts to help us navigate through the world. We have developed maps for the atmosphere, oceans and land; maps for the design of machines and cities, and maps for networks of information flowing through the global internet. We now have instant access to maps that we can use to locate ourselves almost anywhere in the world.

The Mapmakers

As a survival mechanism, humans have become markedly adept at generating and internalizing experienced reality and then structuring it by constructing mental maps. We don’t just experience the world, we interpret it, name it, and give it structure and meaning. Our maps - cognitive, emotional, social, and symbolic - influence how we understand, react to, and communicate about the world. They influence our decisions and guide how we create and follow a life path.

One way to think of our internal maps is that they are two-way mirrors that filter reality as it comes through our senses and filter our communications that we pass back into the world. As we interpret our filtered reality based on our values and beliefs, we create meaning, identity, and a sense of purpose. Without such a map a person could easily become lost in an endless maze of almost infinite choices, losing the ability to function effectively and finding themselves afloat in a sea of meaninglessness.

Our sense of meaning is limited because our maps are simplified representations of reality that are deeply personal and unique. As the B-52’s said we each live in our own private Idaho. No map can ever fully represent the complexity of the actual world as each is partial and subjective. As a result of our interpretations what seems obvious or true to one person may not exist in someone else’s experience and therefore cannot be recognized as having any meaning. An example is someone speaking in a foreign language that you do not understand.

We shape our filtered, construed version of the world by using the tools of our experience: the beliefs, memories, values, culture, and language we encounter when growing up. As we become more adept at refining our maps and communicating meaning out into the world, we become more enamored of and attached to our maps as the right way to live. As we grow, develop, and gain more and more success using our maps, we become trapped in the paradox of our own making: our attachment to our map grows while our alignment with actual reality decreases. We begin to assume that our map is the only right way to interpret the world because it has worked so well for us, blinding ourselves to the maps of others.

Fixed mindsets have been a normal part of human existence for many thousands of years, especially in small villages where change was slow and infrequent. Before the rise of agricultural settlements and writing, we relied on primitive technologies for subsistence. Interlocking families were the dominant influence on our map making. We were powerfully influenced by living within a set of family-based beliefs, where values were revealed through stories.

Families were embedded within cultures, religions, and societies, each of which strongly affect the internalizing of pre-drawn maps derived from tradition and reinforced by the family structure. Widely shared ways of seeing the world were oftentimes a complete and integrated whole that showed logical consistency with external reality in a specific time and place. Such maps generated strong emotional connection, and offered a source of symbolic and social meaning. Even today organized religions throughout the world offer many good examples of pre-drawn maps that foster a strong feeling of attachment.

The rise of agriculture and writing enabled humans to move beyond subsistence living. We became more involved in political life, defining different ways to distribute power and property in society. As we began to project our family-based maps out into the political arena the conflicting versions of individual maps became more apparent. The influence of families and communities remained strong however, which generated an inherent conflict between different political systems, many reflecting the maps of those who sought power and influence rather than an amalgamated map dedicated to the common good of an entire society.

The Big Change

The Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution changed everything. The maps that we had assumed for centuries were the right way to interpret the world were no longer relevant as reason and logic took over as modes of existence. Science emerged as one dominant source of truth, one that had questioning reality – including revered traditions – as the basis of its moral foundation. Another source of truth arose from the rise of capitalism, which holds that the accumulation of material wealth through consumerism is the right way to live, and that the ideals and methods of science are best subsumed to support this highest good.

Along with the rise of reason came a shift in what was considered right and proper behaviors. Rather than achieving excellence in a fixed role that was defined by a small society, along with the moral motivation to sustain the relationships that supported this excellence, humans began to shift into reason-centered behaviors. Once societies were sufficiently organized to move the majority beyond subsistence living, the rise of political institutions furthered the disconnect from pre-defined roles. Such a way of living was missing the moral basis that had served to structure the maps of countless generations.

For the first time people became unmoored from the traditions and locations that had been the foundations of their existence. People were free to create their own maps without having to necessarily adopt those pre-drawn by their family, society, or religion. This rise in individualism was accompanied by the creation of billions of different internal maps, sometimes conflicting, sometimes in alignment, and sometimes sharing the meagerest of similarities. Suddenly the variety and structure of human maps exploded, with each person clinging to theirs as if their life depended on it, which in some cases it did.

Unfortunately, in our present-day complex societies we are given little clarity or guidance in establishing our own map that will guide us to success in our life. It is ironic that we now have access to almost all the information that humanity has gathered over the millennia, yet we lack the ability to parse this information wisely. We are given no lessons in how to create a meaningful life in alignment with our innser map. As a result, many people choose to adopt pre-drawn maps from religions and other organizations.

Our Fundamental Attribution Error

Ultimately, as we live within the confines of our map, all we experience is ourselves projecting our map out into external reality. Thus, we exist within a self-referencing universe, where we assume that our map is the territory, and that our worldview is the only valid truth rather than just another truth, one among many. Even though we may share elements of our map with millions of others, we still insist that ours is the only meaningful and acceptable reality.

Such attachment to our maps is natural, but we make a mistake when we reject the maps of others as being wrong. This rejection fosters misunderstanding and creates conflicts that are reflected at interpersonal, family, community, and national levels. Strong attachment is also the source of willful blindness where we discount observations and information that run counter to our belief system and invalidate others who operate on different maps.

In our day-to-day living we seek information that confirms our maps as valid. Conversely, we shut out or ignore information that disconfirms our interpretation of reality. Since it is very uncomfortable for us to admit that we are wrong because it invalidates our chosen identity, we cling to our map and refuse to believe that the maps of others have enabled them to realize success in their lives, perhaps in different ways from our success.

When we adopt a strongly reinforced pre-drawn map or become too attached to our own personally developed map, we unconsciously engage in what is known as othering: categorizing those who do not share our maps as strangers. We instinctively regard strangers as someone who might be dangerous, a competitor, or disease-ridden so we approach them with caution and some degree of fear. Adopting pre-drawn maps creates group identities that differentiate one’s group from other groups, us from them, and can reinforce suspicion or fear of outsiders.

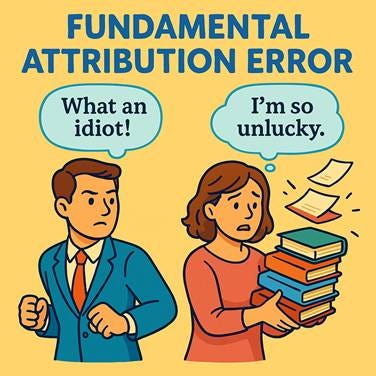

Even if a person chooses to make their own map, they will usually adopt some of the practices found in their community and society, thus creating a weaker form of shared reality and group identity. Our brains use heuristics, which are mental shortcuts, to make fast judgments. When we see familiar faces these shortcuts trigger recognition and trust. But when it comes to strangers, these shortcuts activate uncertainty and can lead to bias or fear. When we observe others behaving in ways we consider confusing, irrational, wrong or hurtful, such fear can severely distort our understanding and lead to a form of the fundamental attribution error.

This error occurs when we assume that someone else is doing something - especially something negative - because of who they are, not because of the circumstances they're in. Conversely, when we encounter a difficult situation, we blame circumstances instead of who we are and how we behave as causes.

This error is compounded when we forget that no map can ever fully represent the complexity of the actual territory, and that every map is a simplified, partial, and subjective version of actual reality. When we forget this and think that our map is the only true representation of reality, we decide that our right and wrong is what is right and wrong for everybody. Since we need to feel secure within ourselves and our adopted identity, we judge others as bad people.

Compounding this error is our assumption that our survival depends on holding fast to our map for as long as possible and on rejecting information that disconfirms our version of reality. This assumption may work within a relatively cohesive group where everyone shares most of the elements of their mental maps. Where it breaks down is in a modern democracy, a multi-cultural setting or simply living in a large city where we are likely to encounter strangers on a regular basis.

Finding Freedom

We first find freedom through our interpersonal relationships with others and with our communities. We find freedom when we acknowledge the maps of others by seeking first to understand, then to be understood. This approach requires an attitude of curiosity towards others, who we can approach with humility and compassion in recognition of their essential shared humanity. We can pause before judging others and consider what unseen pressures or circumstances they might be facing. Seeking first to understand also supports flexible thinking, which is key in conflict resolution and leadership.

We take the second step towards finding freedom through our social institutions. These are, both locally and nationwide, projections of our mental maps onto systems and processes that reflect our inner priorities. This projection creates both clarity and constraints on freedom simultaneously. We find our freedom in the recognition that personal freedoms may be limited to achieve social stability while making sure that our essential values are reflected in our institutions.

For example, the US Postal Service, by connecting everyone through a shared institution where everyone, regardless of their background, has the freedom to reach out to others through letters and packages, evokes a sense of democracy and belonging. We can send letters and packages that capture snapshots of our lives and remind us of people, eras, and emotions in the past. The Postal Service has become a cultural icon, with mail carriers as everyday heroes, stamps as works of art that reflect our values, and post offices as local landmarks.

The postal service reflects how we anchor our identity in a widely shared institution that reflects our national myths, history, and language while allowing space for multiple narratives. It is an institution that supports the free expression of both our individual maps and our shared collective maps. It supports richer, person-centered understanding as we reach out to each other.

Many of our other social institutions such as schools and universities, courts and civil liberties organizations, independent journalism and public television, and museums and theaters also support the free expression of both our individual maps and our shared collective maps. In today’s rising authoritarian environment, however, they are under strain or being degraded due to economic and political power grabs, which have arisen largely due to the influence of large organizations dedicated to the pursuit of financial profit. These organizations have become monopolies and have amassed enormous economic wealth, along the way becoming highly adept at translating this wealth into political power that threatens our democratic form of self-government.

Many of these organizations are organized as for-profit, publicly held corporations, and are structured as extreme hierarchies in direct opposition to the more democratic social institutions found throughout our society. They have been allowed to grow uncontrolled over the past 45 years due to lax enforcement of the anti-trust and monopoly laws.

Today these corporations practice what is known as regulatory capture, where their outsized influence on campaign financing and lobbying results in essentially an overthrow of the public’s interests in favor of corporate share price. Corporate control over our lives frequently results in rigidity, misjudgment, and sometimes harm. These corporations place an overreliance on metrics, chasing numerical targets as if they fully capture social well-being while ignoring deeper systemic issues such as pollution, social justice, and climate change. Many adopt financial models that assume rational behavior or frictionless markets, which results in misguided strategies that isolate people and deepen overall social inequality.

Living inside these corporations influences our thought patterns in subtle and hidden ways. Over time these thought patterns degrade our ability to live as free human beings. Although the hierarchical nature of these corporations is an efficient way to move material goods and services throughout the economy, such hierarchies systematically reject employee and stakeholder individuality. When we live inside corporations for most of the time, we become drone-like and our thought forms become rigid. We make poor decisions that may seem rational at the micro level but degrade our essential human freedoms at the societal level. The limited perspective we are forced to adopt to function in a rigid hierarchy causes us to deny the existence of our own maps while trying to live out a role pre-drawn for us in the maps of the owners and managers of the corporation. Over time, we begin to regard this denial as normal, and we begin to think that mistaking our maps for the territory is an acceptable way of being.

So the second step in finding freedom is to recognize the limitations that our social institutions may have placed on our thinking patterns, and how we may be unconsciously limiting acceptance of both our maps and the maps of others. Then, we can use this understanding to support those institutions that promote individual dignity and freedom of expression. For example, in business we can create Benefit-Corporations and employee-owned companies, and in our lives, we can support independent journalism, theater and literature programs, and arts organizations.

Our goal should be reinterpreting and challenging established social institutions that assert that their map is the only correct one. We should challenge unconsciously adopted models of thinking that cause us to declare that our organization’s map is the only correct interpretation of the world. We should provide ongoing support for organizations that allow space for multiple narratives.

By doing so we remind ourselves that no one has a monopoly on truth, and we honor the difference between perception and reality. We find our freedom by creating room for dialogue instead of fear and division, learning instead of closed-minded judgment, and understanding instead of misguided certainty. We thus become active participants in the ongoing construction of our American identity, building on the free expression of shared myths and history, a great work that is never complete.